This week, President Biden announced a student loan forgiveness plan that includes canceling up to $10,000 in student loan debt for those earning up to $125,000 in annual income ($250,000 for a married couple) and up to $20,000 in loan forgiveness for Pell Grant recipients.

The student debt cancellation program is estimated to cost $330 billion over the next ten years, costing the average taxpayer an estimated $2,500.

The announcement has drawn praise and criticism. No matter where you stand on debt forgiveness, one thing is clear: it doesn't address soaring college tuition costs.

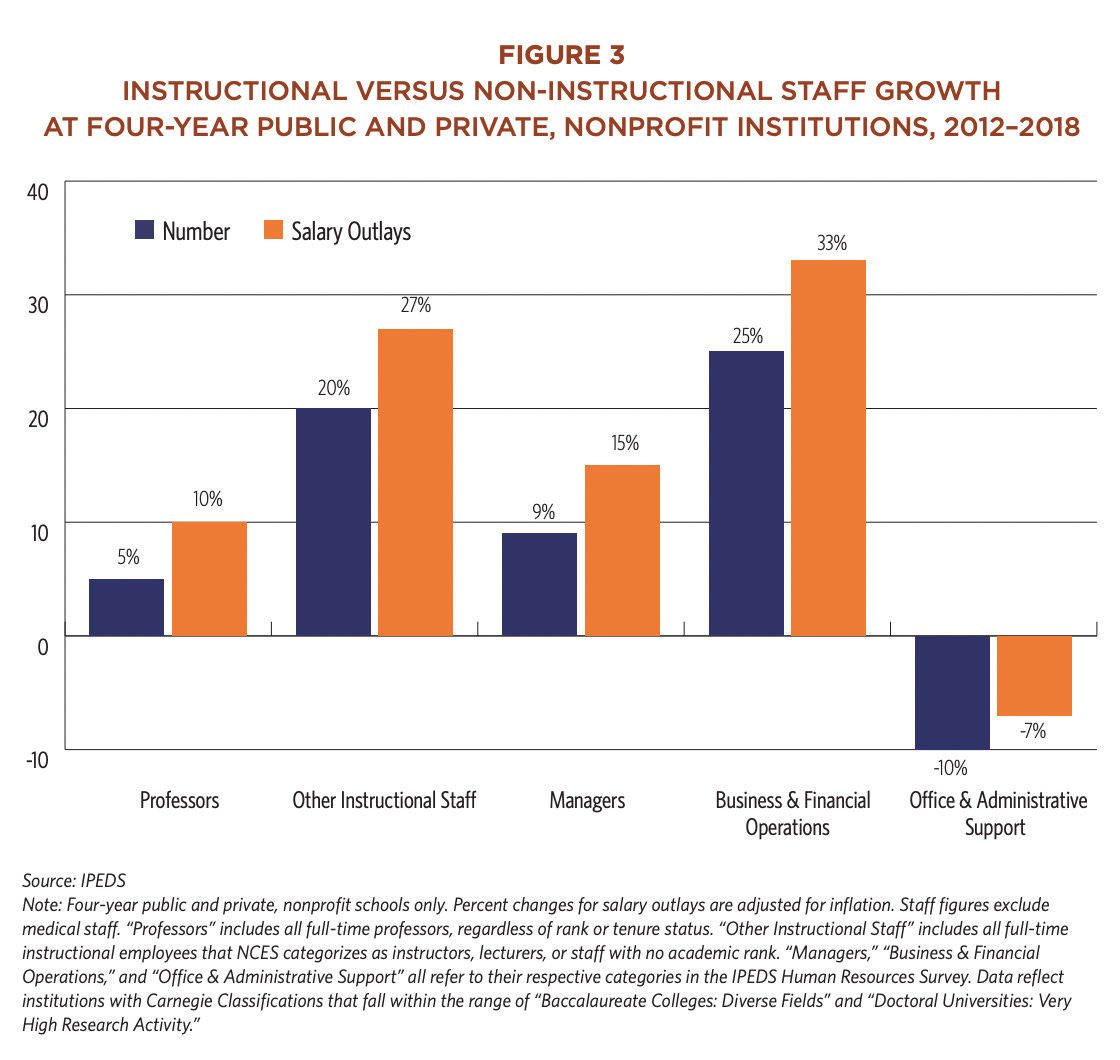

It’s well-documented that costs are being driven by the “administrative bloat” phenomenon in higher education, with spending on administration and student services outpacing expenditures on instruction. While spending on instruction has grown, universities and colleges are placing less emphasis on full-time instructional staff and hiring more adjuncts, according to the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA), which released a detailed report last year on runaway college spending.

According to ACTA, the cost of four-year public tuition has risen 178% since 1990.

“Even the most optimistic would be hard-pressed to argue that colleges today are providing nearly three times the educational value that they did 30 years ago,” the ACTA report said before noting, “This argument crumbles in the face of studies that show that one-third of students leave college without any growth in critical thinking or analytical reasoning skills and that only 49% of employers think recent graduates are proficient in oral and written communication.”

As the ACTA report puts it: “debt cancellation is but a temporary solution that treats the symptom and not the disease.”

And this disease has other consequences on campus, especially around free speech.

It’s a topic that came up on a recent podcast episode with prominent First Amendment attorney Greg Lukianoff, a New York Times best-selling author and the President and CEO of The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (previously called the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education). FIRE is a civil liberties nonprofit that started to protect free speech rights on college campuses in the U.S. and recently expanded its mission beyond campus

As described above, Lukianoff also pointed out that the hyper-bureaucratization of campuses is driving tuition costs.

“You’re not paying for universities that have way more professors than they had 20 years ago. You’re paying for universities that have way more administrators,” Lukianoff told me.

Moreover, the rising cost of college tuition driven by this administrative bloat directly relates to the decline in free speech on campus.

“Most importantly, the increase in tuition and overall cost is disproportionately funding an increase in both the cost and the size of campus bureaucracy, and this expanding bureaucracy has primary responsibility for writing and enforcing speech codes, creating speech zones, and policing students’ lives in ways that students from the 1960s would never have accepted,” Lukianoff wrote in his book “Unlearning Liberty: Campus Censorship And The End Of American Debate.”

Lukianoff told me that those administrators, especially in Residence Life, “see as part of their job that they police speech on campus.”

“[This] is one reason why I was so concerned about the idea of doing debt forgiveness without any attempt to de-bureaucratize universities. We can’t keep having these institutions getting more and more bureaucratized more and more expensive over the years,” Lukianoff said.

Lukianoff added that a less bureaucratic university “could be not just a cheaper university, but also one that’s more free — that has more freedom of speech and more due process.”

Lukianoff, a lifelong Democrat, is passionate about free speech and has been defending free speech on campuses for more than two decades. It’s a pronounced problem too. There have been 711 attempts to get professors fired since 2015, and about two-thirds of those attempts resulted in punishment.

“We’re talking about hundreds of professors who have either stepped down or been fired. Three dozen of them, at minimum, are tenured professors. Now, when I started, a tenured professor losing their job for what they said or what their research said or for what they taught was unheard of,” Lukianoff said.

During my hour-long conversation, I also learned from Lukianoff that 2020 was the worst year for free speech on college campuses, even during lockdowns and remote learning. FIRE typically sees 1,000 case submissions during a “busy” year, but amid the shutdowns, that number rose to 1,500, up 50% from the busiest years. To be sure, Lukianoff noted the fever appears to be waning, but reforms are still needed.

“I do think that it can’t keep up as intensely cancel happy as it was in 2020, and there are some signs that it’s starting to abate a little bit, but unless we make meaningful reforms this time around to protect free speech on campus and off it’s only going to be worse next time,” he said.

Beyond addressing the hyper-bureaucratization of universities, Lukianoff suggested a list of six things people can do to protect speech on campuses, which include:

Ask your alma mater to get rid of speech codes.

Tell university presidents to stand up for students and professors, early and often, when they get in trouble.

Adopt an academic freedom statement for the age of social media (similar to “The Chicago Statement”).

Have an orientation that explains freedom of speech, which is a sophisticated concept, particularly regarding academic freedom.

Poll students and professors to assess the campus environment.

Consider alternatives to college.

“I think that the idea that we’re sending people — your sons and daughters —to schools that try to argue that $70,000-a-year only covers half the cost of educating one student for one year, I think is ridiculous. I think we have to figure out better ways to signal to employers that this person is hardworking, is smart, and actually knows statistics, writing, etc.,” Lukianoff added.

Another recommendation from Lukianoff: take a gap year.

“They [students] should be doing something for at least a year, preferably having something that involves some autonomy, some independence from their parents, some real challenge and hard work. Because what’s happening now is we’re sending students to campuses without enough personal experience, without a sense of what’s called self-efficacy — the idea that they can handle themselves on their own. And it’s bad for mental health; it’s bad for academics; it’s bad for campuses in any number of ways. So, I believe strongly in a gap year, particularly if that year involves real work.”

Lukianoff is the author of Unlearning Liberty: Campus Censorship and the End of American Debate, Freedom From Speech, and FIRE’s Guide to Free Speech on Campus. He co-authored The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure with Jonathan Haidt. He’s working on his next book Cancelling of the American Mind, with his co-author Rikki Schlott.

Listen to the full episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen. Watch the full episode on YouTube.